Karnpuka

- Words by

- Zena Cumpston

WHEN I WAS YOUNG, my mum discovered a quandong tree close to our house – the thirty-ninth she had lived in since marrying our grass-is-greener eternal-wanderer dad – deep in Adelaide suburbia. Her excitement was curious to me; she was almost crying with joy. I wondered how good this fruit could possibly be to provoke such an exuberant, full-body reaction. She collected lots and made a jam. Her ingrate children, including me, rejected it: too tart for our deeply Westernised palates.

On my Barkandji homelands, we see our plants and trees always through their interrelationship with us, always as a part of our cultural landscapes and within the holistic web that is Country. Cultural landscapes encompass the natural environment, the spiritual and traditional knowledge of that environment, and the cultural practices and activities applied across many millennia of dynamic interactions between people and Country. In direct contrast, the Invaders mostly viewed these landscapes through a lens of extraction and capitalism – much of the reason they came to this place was to harness and plunder resources. For them, plants were integral in giving these stolen lands their all-important (Western) economic foundation through the establishment of European agriculture and trade industries.

Today, the erasures effected by the ongoing circumstance of colonisation have not allowed broader Australian society, and especially those who hold power, to recognise and to understand the depth and breadth of knowledge embedded in the cultural relationship between Australia’s First Peoples and Country. Australia’s indigenous plants were key to the colonising project, collected, classified and utilised for industry in a multitude of ways, from river red gum and many other indigenous trees used as a building tool, to plants used for tanning and as fuel. While the newcomers benefited from our plants, they most often did so in ways that were damaging to Country.

We, as the First Peoples of Australia, most often view plants not as a resource, but as kin, to be actively cared for as part of our custodial responsibilities. For us, plants have been the absolute cornerstone of life and longevity for a timeframe that extends far beyond the last 200-ish years, into forever.

Quandong (Santalum acuminatum) is a much loved and culturally important tree on my Barkandji Country, as it is for many diverse Indigenous communities across a wide expanse of Australia. While quandong also grows in some southern parts of the Northern Territory and Queensland, its natural distribution is predominantly across the southern regions (spanning from the south-east to the south-west) of mainland Australia. Fruiting between August and December, with slight variation across landscapes, quandong are sometimes known as wild peach, desert peach or native peach. The word quandong is thought to have derived from the Wiradjuri word guwandhang. In our Barkandji (Paakantyi) language we know them as karnpuka but we use the common name quandong also; a word in widespread use, having developed as an example of Aboriginal English.

Quandongs are hemiparasitic: in order to grow they must attach themselves to a host plant, most often acacia and saltbush. This renders them somewhat challenging to propagate and to make commercially viable, but in many places quandong trees appear to grow in groves – evidence that diverse Aboriginal communities across a range of landscapes learnt to successfully propagate and plant them, making them available en masse. Deep knowledge of Country and the quandong tree enabled skills to make this important food source abundant.

Our cultural landscape also attests to the symbiotic relationship between animals and plants on Country – the emus consume seeds from a vast array of plant species, including quandong, and disperse them over long distances. We rely on the emu for food; its meat and eggs, but we also have a reciprocal relationship with it as a totemic species that we must care for and respect, never taking too much, for to do so would harm the balance of Country and its complex webs of interrelationship.

Because they grow well in arid and semi-arid conditions, and are a drought tolerant and reliable food source, quandong trees are highly valued. It is not just their hardiness and consistency that positions them within an important cultural realm, they are also highly prized for their many beneficial uses: nutritional, medicinal and technological. The tart, sometimes sweet and tangy fruit can be eaten raw, and also dried to be kept for extended periods. It can be made into jams, chutneys, sauces and pies, and is sometimes used to make a sweet and refreshing drink. Most often eaten in spring when fruits are ripe and red, it can also be eaten green if roasted.

As well as having significant antimicrobial properties, quandong fruits – which are higher in vitamin C than oranges – have high levels of folate and vitamin E, and are also a good source of magnesium, zinc, calcium and iron. The wood from the quandong tree was used to make powerful clubs, fire drills and ornamental items such as carved animals. The seeds are used by children to play games similar to marbles and are also used in body adornment and for making jewellery such as necklaces. The quandong seed has a nut, and the kernel inside is of great medicinal and nutritional value, but before being eaten must be roasted. Once cracked open, the kernel can also be ground and used as hair conditioner and as a balm to soothe scalp conditions. The balm made from the kernel is also effective for relieving aches and pains. Bark shavings from the quandong tree can be soaked and the liquid used to relieve itchiness. The outer wood of the tree can also be made into a decoction to soothe chest complaints, and an infusion of the roots relieves rheumatoid conditions. The leaves of the quandong tree can be smoked to clear away mosquitoes, and the smoke from this leaf is utilised to improve strength and stamina.

Quandong stones were ingeniously invented to crack and process the nut. Often referred to as ‘nut crackers’ by Aboriginal community members, these stones are known to have been used to separate the valuable kernel from the nut and archaeological research shows the evidence of large-scale processing.

Their appearance on Country when in fruit makes me feel they are showing off, much like an interloper – beautiful, richly coloured crimson fruit popping across a backdrop of muted, smoky, arid tones, looking as if someone has carefully decorated the tree with festive baubles. I can imagine mobs thrilled by this scarlet signpost, energised to fill their bellies, to work together to process and store this highly valuable and delicious bounty.

Today I would do almost anything to try Mum’s quandong jam again, properly understanding only now, thirty-plus years later, what it meant to her. That it signified her longing for the embrace of home, cherished memories of childhood. Country. Culture. Family. Ancestral connection. And now for me, thanks to this childhood memory, quandong will always remind me of my mum, of the richness of Country, and our people’s deep knowledge of it.

–

Special thanks to Emeritus Professor Lesley Head who co-wrote my book Plants: Past, Present and Future (Thames and Hudson, 2022). Many of the narratives explored here were greatly aided by Lesley’s sharing of resources and ideas as part of our collaboration. Also special thanks to Barkandji/Barkindi community members Uncle Badger Bates and David Doyle, who have generously shared with me much cultural information about our relationship to quandong on many trips together on Country.

READING LIST

Wonderground typically doesn’t publish footnotes or references. However, while things are much better than they have been, none of us are learning as much as we should be in schools, universities and workplaces about Aboriginal people and culture. It’s important to me to share relevant resources as part of all my work, to aid those who wish to learn more. Please skim or delve deeper if you wish.

– Zena Cumpston

BOOKS

Aboriginal People and Their Plants, Philip A Clarke, 2011, Rosenberg Publishing

Aboriginal Plant Collectors: Botanists and Australian Aboriginal People in the Nineteenth Century, Philip A Clarke, 2008, Rosenberg Publishing

Australian Native Plants: Cultivation and Uses in the Health and Food Industries, Edited by Yasmina Sultanbawa and Fazal Sultanbawa, 2016, CRC Press

Bush Food: Aboriginal Food and Herbal Medicine, Jennifer Isaacs, 1987, Lansdowne

Jewel of the Australian Desert, Native Peach (Quandong): The Tree With the Round Red Fruit, Neville Bonney, 2013, self-published

Koorie Plants, Koorie People: Traditional Aboriginal Food, Fibre and Healing Plants of Victoria, Nelly Zola, Beth Gott & Koorie Heritage Trust, 1992, Koorie Heritage Trust

Plants: Past, Present and Future, Zena Cumpston, Michael Fletcher, Lesley Head, 2022, Thames and Hudson

The Useful Native Plants of Australia, Joseph H Maiden, 1889, Turner and Henderson, Sydney

JOURNAL ARTICLES

‘From Songlines to genomes: Prehistoric assisted migration of a rain forest tree by Australian Aboriginal

people’. Maurizio Rossetto et al, 2017, Plos One

‘Quandong stones: A specialised Australian nut-cracking tool’. Colin Pardoe, Richard Fullagar & Elspeth Hayes, 2019, Plos One

‘The emu: More-than-human and more-than-animal geographies’. Margaret Raven, Daniel Robinson, John Hunter, 2021, Antipode

–

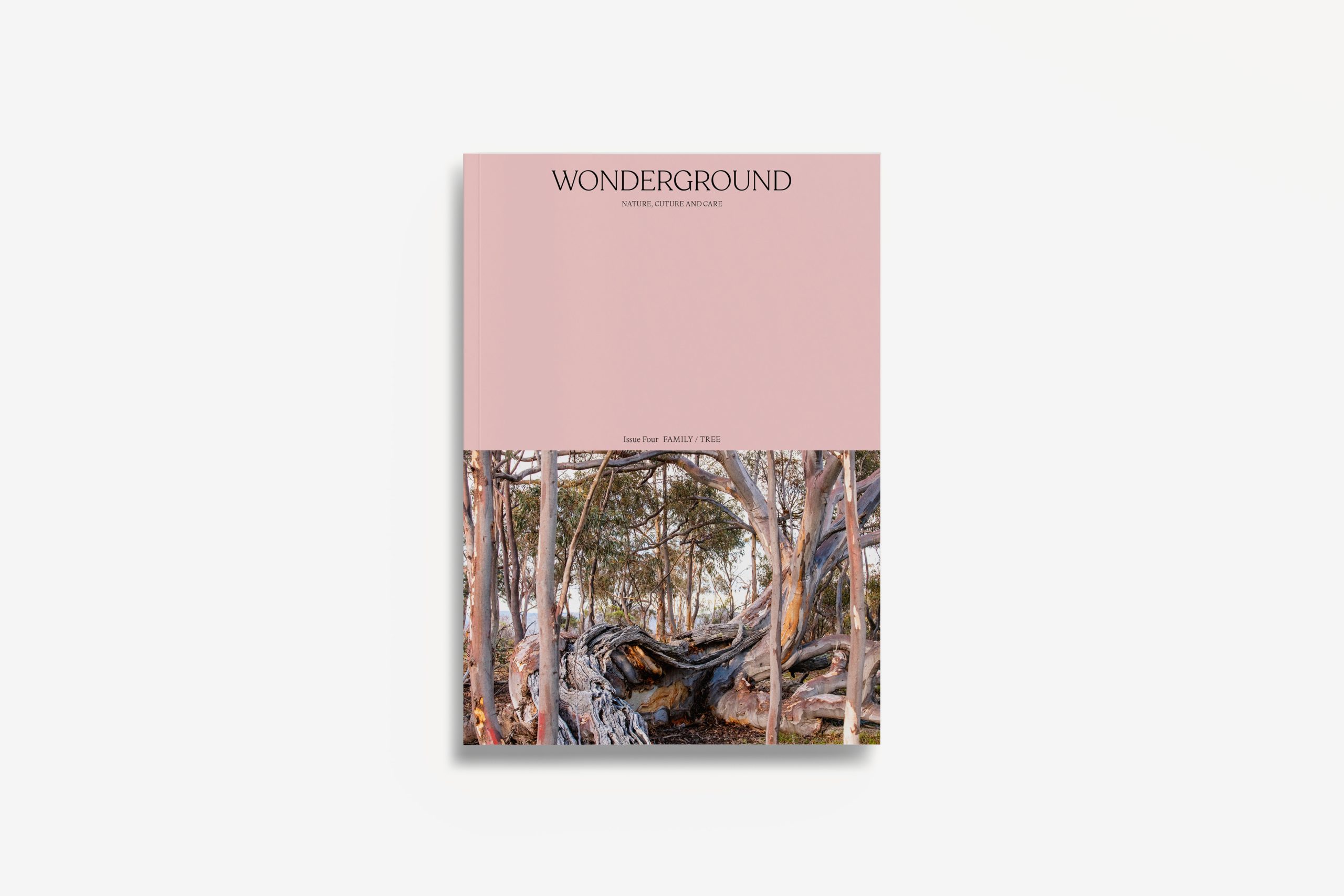

Header image: Quandong (Santalum acuminatum) fruit. Photo: Suzanne Long/Alamy Stock Photo.