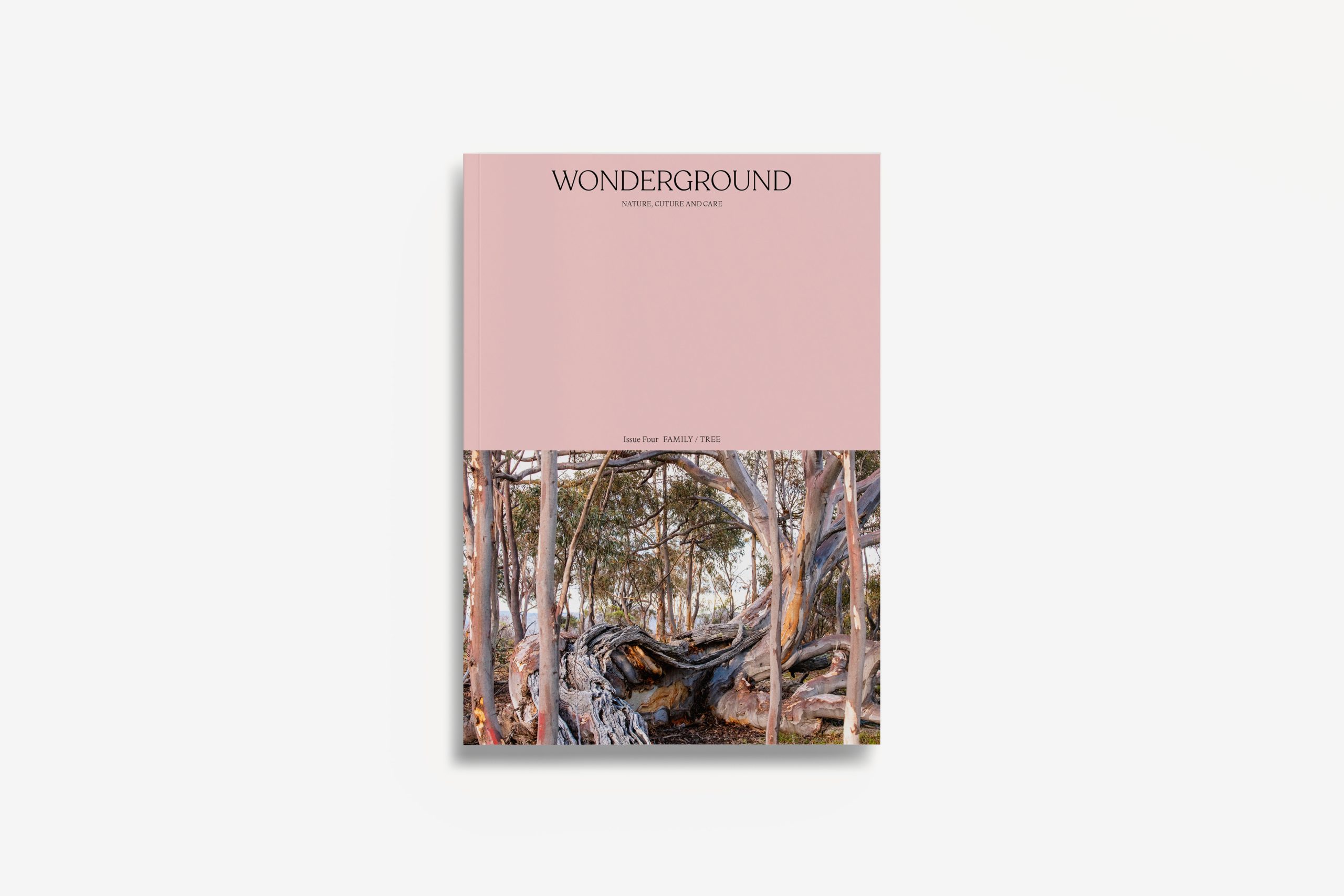

Root and Branch

- Words by

- Neha Kale

A family isn’t limited to a group of blood relatives. It’s also about inheritances that are invisible and intangible or hidden genealogies that involve the natural world. Here, Wonderground profiles three artists who re-imagine ideas of kinship and ask us to look closely at ties that bind.

TIYAN BAKER

The jungle, in the colonial imagination, is a place to explore and conquer. But for Tiyan Baker, whose mother is Bidayǔh, part of an Indigenous community with roots in southern Sarawak, it’s deserving of reverence, subject to secrets and codes. ‘My family has always said, “Don’t go there alone, a ghost is going to take you”,’ she says. ‘You’re not supposed to wear bright colours or talk loudly. The jungle is full of this very evocative kind of danger.’ She laughs. ‘I think that sort of fear is actually very reasonable.’

In her work, Baker, who identifies as both Bidayǔh and Anglo-Australian, traces the unseen relationships between language, places and stories. Her video works, installations and photographs centre Bidayǔh culture. But they are also interested in the things we unknowingly inherit. All that can shift, be mistranslated or lost.

To make the 2020 video work Tarun, originally commissioned for the moving image platform Prototype, Baker returned to her mother’s Sarawak village, colonised by both Britain and Malaysia. She listens to her recount her journey of migrating to Australia in Bidayǔh, while working in the padi fields, sitting near a waterhole. Then, as the jungle looms in the distance, she learns to haltingly repeat her mother’s words.

‘I wanted to pull together her past and my present,’ she says. ‘The conceptual trick of speaking her words with my mouth [was] a way to explore time.’

Time is a strange phenomenon. It can distort memories and perceptions. When Baker was a child, she was obsessed with solving Magic Eyes, patterns of dots and textures that conceal 3D images. For nyatu’ maanǔn mungut bigabu (2021), a series that won the 2022 National Photography Prize, she revisits her mother’s ancestral farmlands. She transforms scenes – fields of durian, lush green foliage – into Magic Eyes, embedding each image with a forgotten Bidayǔh word.

‘To me it is about relearning to see the landscape a certain way,’ says Baker, who’s currently working towards a solo show, My Mother’s Tongue, at Melbourne’s Bus Projects. ‘There is language loss, but I’m reclaiming it. If you put your eyes the right way, put your body the right way, you can see the language the landscape is offering.’

DIANA SCHERER

Diana Scherer. InterWoven #11, 2019. Soil, seed. Diana Scherer. Entanglements, 2020. Corn, soil, plastic net, synthetic fibre and textiles.

Often, trees command an upward gaze. We admire the sturdiness of a branch. Bask in the light that trickles through a canopy. But for Diana Scherer, a tree’s power is subterranean. It unfolds below the surface. Over a decade ago, Scherer, whose grandparents were farmers, started studying root systems. To her, these underground tangles of tissues, hairs and fibres reflected the human desire to control nature. But they also revealed nature as artist and collaborator, with intelligence of its own.

‘A root navigates, knows up and down, perceives gravity and can locate moisture and chemicals,’ she says. ‘Roots are incredibly strong – they fight for food, for the very space they find.’

Scherer, who started out as a photographer, transforms root systems into living textiles. In 2016, she started work on InterWoven. For a 2021 presentation of the project at Germany’s Frankfurter Kunstverein, she sowed oat seeds on fabric. Hours before the exhibition opened, she revealed the roots, highlighting their intricacy. The work is also a lesson in the ephemeral: witnessing their beauty as they wither over the course of days.

‘The bare root system presented as textile or as a living sculpture shows traces of a reckless intervention in a natural system,’ she explains. ‘But it also shows a concept for a possible cultivated path together. I do not want to answer questions or find solutions. I want to approach the theme in a poetic way.’

At the 2022 Biennale of Sydney, Scherer showed Entanglement. The installation, presented at Barangaroo’s Cutaway, explored xylem vessels – the tissue responsible for ferrying water through plants. ‘The starting point [for the work] was the microscopic anatomy and cell structure of plant material,’ she says. ‘My focus was on the strategies of the internal “waterways” of plants. The emergence of xylem is considered one of the most important innovations in plant evolution. Plants are intelligent organisms despite their silent, seemingly passive appearance. They react to the world, make decisions and cooperate with each other.’

LÉULI ESHRĀGHI

Enlightenment thinking carved the world into pieces. But Léuli Eshrāghi believes that new forms of ritual can transform our relationships with each other. It can also reimagine what counts as kin. In 2020, Eshrāghi, an artist, writer and curator of Sāmoan, Persian and Cantonese ancestry conceived re(cul)naissance for NIRIN, the 2020 Sydney Biennale. The work features a textile installation that evokes an eight-limbed fe‘e deity, the octopus god of war in Sāmoan mythology.

The work hovers, like a shrine, over a neon pool of water. For Eshrāghi, it recalls a pre-colonial sense of connection between the human and non-human. It centres joy in the process.

‘I wanted to delve into pleasure, passing through grief from present and past traumas, that I believe my ancestors across the Great Ocean enjoyed in a truly embodied way,’ they say. ‘I think we have to be brave and responsible, so honouring kinship with entities in the world is key.’

Earlier this year, Eshrāghi was involved as a scientific advisor for Reclaim the Earth at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, an exhibition that knitted together ecology, feminism and Indigenous politics. The show explored Rachel Carson’s idea that we all exist as part of a ‘soil community’. ‘The binary of nature/culture is an invention of Western Europe just as the heterosexual/homosexual, deviant/ pious, civilised/savage binaries are falsehoods that still serve those few people with immense material and cultural privilege,’ they explain.

When we speak, the video work AOAULI (VILIATA), part of the Siapo viliata o le atumotu series (2020), shows as part of A Clearing in the Forest at London’s Tate Modern. In the work, the artist’s body, marked with tatau – the Sāmoan tradition of tattoo – seems to shimmer like a mirage, its edges disappearing into the sun-bleached earth around it.

‘Realising that we are already beings who are the sum of thousands of communities that have survived gives me the drive to create new ceremonies for the crises we are living [through], among so many other species on this watery planet,’ they say.

–

Image top: Tiyan Baker. maanǔn (found all over the place in plenty), 2021. From the series nyatu’ maanǔn mungut bigabu. Digital autostereogram print on cotton rag.