The Poem that Saved a Forest

- Words by

- Georgina Reid

Jacqueline Suskin is a poet. Neal Ewald is an industrialist. Jacqueline loves trees. Neal is in the business of cutting them down. The pair are great friends. In 2014, their unlikely bond resulted in the preservation of 1000 acres of redwood forest for community use in Humboldt County, California.

Here’s how it happened: For many years, Jacqueline ran a performance-writing project called Poem Store. Each week she’d set up her antique typewriter and a sign reading Poem Store. Your Subject, Your Price at a market in Arcata, California. People would come and ask for a poem and Jacqueline would oblige. One day, a man came along and asked for a poem about being underwater. Jacqueline obliged and the man was delighted with her words. He took her card, and a few days later she received an email requesting a poem for his wife, who had died of cancer two years earlier. He wanted something to read when he and his children spread her ashes at sea. ‘I took a deep breath. I’d gotten all kinds of requests at Poem Store but never one so sad and heartfelt.’ The man mailed her a book that his family had put together about Wendy, his late wife, and Jacqueline wrote him a poem.

It was not until Jacqueline emailed the man requesting that they meet for her to present the poem to him in person, that she realised who he was. His email signature read, ‘Neal D. Ewald, Vice President and General Manager, Green Diamond Resource Company’. ‘I froze. Green Diamond was one of the most controversial timber companies still doing business in northern California. Just recently, environmentalists had staged treetop sit-ins to protest the company’s plans to log and build houses on a prime 7500-acre parcel of redwood forest near Arcata called the McKay Tract.’

Jacqueline swallowed her misgivings and met Neal for dinner. And so began a firm friendship. Through their relationship, Jacqueline inspired Neal to connect with environmentalists who were staging a sit-in in the forest. In 2014, following engagement with activists, county officials and an organisation called The Trust for Public Land, Green Diamond cancelled its plans to log and develop the McKay Tract and sold 1000 acres of lush redwood forest to the county, to be preserved as public parkland. This is how a poem saved a forest.

There is a neatness to this story. And it’s captivating. But it’s only one side of the coin. I catch up with Jacqueline Suskin in late 2020, six years on. Because, at this particular time, it feels important to elevate and explore stories of connection – of opening, not closing, doors to different people, ideas, world views. But as Jacqueline soon pointed out, the outcome of dancing in the spaces between black and white is not clarity, instant gratification or simple solutions, but a messy jumble of hope and despair, action and inaction, change and frustration. Perhaps learning to find meaning amid the mud and the muck of the in-between is the real work.

Georgina Reid: I’m fascinated by this story, Jacqueline. It must have been an amazing feeling when the forest was handed over to the community. I wonder, what has happened since then?

Jacqueline Suskin: I’m still friends with Neal, we’re still super close, we hang out and talk a lot. But I always thought that we would continue to collaborate and it’s proven to be a lot more difficult to get that going.

I imagined further collaboration, not even necessarily including myself, but between Neal, Green Diamond and the activists who were tree sitters and forest defenders. I was like, ‘There is a way for you to communicate here that could be incredible.’ I was envisioning a future where Green Diamond would transform their practices, and then they would be able to teach the people who worked for their company how to engage with activists in a different way. I was like, ‘Oh, this is great, this will be a perfect example others can follow.’ But the pace of that is not necessarily up to me.

I guess you have to expect that maybe progress will not continue, maybe it will be sequestered to this one place in time and this one tract of forest. And you have to let that be enough. That’s very difficult for me because it is not enough. In the grand scheme of things, it is not enough only to have this one isolated incident. What I want is a replicable piece of progress for other people to say, ‘Oh, that’s how they do this, I can learn from that, now we can do that here with this piece of land, now we can do it here and there’, on and on and on.

It can be unsatisfying to have a moment of potential progress be sequestered to just one moment, but that that doesn’t take away its importance. There’s a balance of understanding – this is something that I’m trying to hold onto right now. It’s like, you can have hope and hopelessness at the same time, don’t ever just have one, don’t ever lean into hope and be like ‘Yes!’ or lean into hopelessness and despair, but have them both at the same time and everything kind of works that way, you know?

And the chance for great progress to come from that incident where this poem saved a forest, it’s still real, someone could read about it years later and be like, ‘Oh, that’s inspiring me to do this thing’, or that could have already happened, who knows?

GR: It has already happened, I’m sure. I’ve been thinking about transformation and change lately, and always I guess. There’s a holding on to the idea of change that sometimes doesn’t feel healthy. I mean, we all want change to happen right now and we feel like it needs to happen right now, but things take time … maybe a generation or more, and we don’t know how much time we’ve got. I think that puts a really big weight on shoulders. That pressure is a tricky thing to hold because, you’re right, we’re holding both hope and hopelessness at the same time, and we have to find some kind of equanimity in that.

JS: Yeah, and I think the only answer we have is to do that, continue our efforts even though we really don’t know what kind of change will happen in our lifetime. We might not see very much. But these little moments, these openings, are still viable.

I think the great importance of the story of Neal and I is that we were able to be open enough to receive one another so that something really great could happen. And that’s the thing – can we show each other again and again that we are indeed open and able to find each other in these spaces? I hope so, I hope that we can continue to do that because from those things, that’s where newness arises.

GR: Now, let’s talk about poetry. I mean, all this happened because of a poem. I’ve noticed in this past year, as our worlds have felt increasingly uncertain and unintelligible, people seem to be reaching towards poetry. People are looking for meaning, I guess, and I think poetry offers space for meaning in a way that perhaps is, like gardening, very open. People can respond to poetry or plants in ways that aren’t necessarily intellectual, but felt and embodied.

JS: Yeah. You said it, it’s an opening. By witnessing Neal and his trauma and the loss of his wife, I gave a poetic response and that showed him that I was open to his whole being, not just the judgmental view of who he is in the world, but him as a human with trauma, emotional grief, loss, all of his experience, not just this limited mindset of him as this big fat cat timber baron.

And in that is an example of just how we can approach each other with all of our differences and knowing that yeah, yeah, we don’t agree on everything, but we probably are sad about the same things or happy about the same things. We really do want a lot of the same things.

The heart of it – and this is what poetry reveals – is that we’re all suffering over the same things, we’re all craving the same things, we’re all celebrating similar things.

Throughout all of my years writing poems, over 40,000 poems, it didn’t matter where I was or what the demographic was, or what part of the world I was in, everybody asked for poems about the same subjects.

GR: What’s the top ten list?

JS: We’re all trying to be loved, we’re all trying to feel safe, we’re all trying to feel purposeful, we’re all trying to figure out which direction we should go and we all are trying to take care of our families, and show up for the people in our lives, or forgive ourselves, or forgive others. It’s all the same story of old.

I think poetry helps people remember that. Like when you see such a deep, old feeling reflected to you in this simplified package of an accessible poem, it just opens you up to knowing all of that.

GR: I’m just thinking that writing poems, writing 40,000 poems for people in the way that you have – that would have been like a university education times a thousand!

JS: I know. Hopefully someone will give me a degree someday. I mean, I have a degree in poetry, but I always think, ‘I’ve earned an honorary PhD or something.’ That happens, poets get that, so I’m like, ‘Give me that!’.

GR: What are you doing now?

JS: I’ve just written a book called Every Day is a Poem. It’s kind of like a guide to seeing the world as a poet sees the world. It’s the next step of getting people to open up even further, to carry that lens for themselves so that I don’t need to write the poem for them anymore. I want them to write the poem for themselves now.

I’m not interested in being a completely esoteric poet. I want my work to be of service. I mean, I would love for people to learn how to look at the world as a poet looks at the world and then maybe they’ll want to save a forest too … The point is just to let everything be a poem and let everything be saturated in meaning.

It’s that mindset that allowed me to see Neal for who he was and then see the potential in connecting with him instead of just closing off, you know? I have changed Neal’s life actually, and I continue to. And he still changes mine.

–

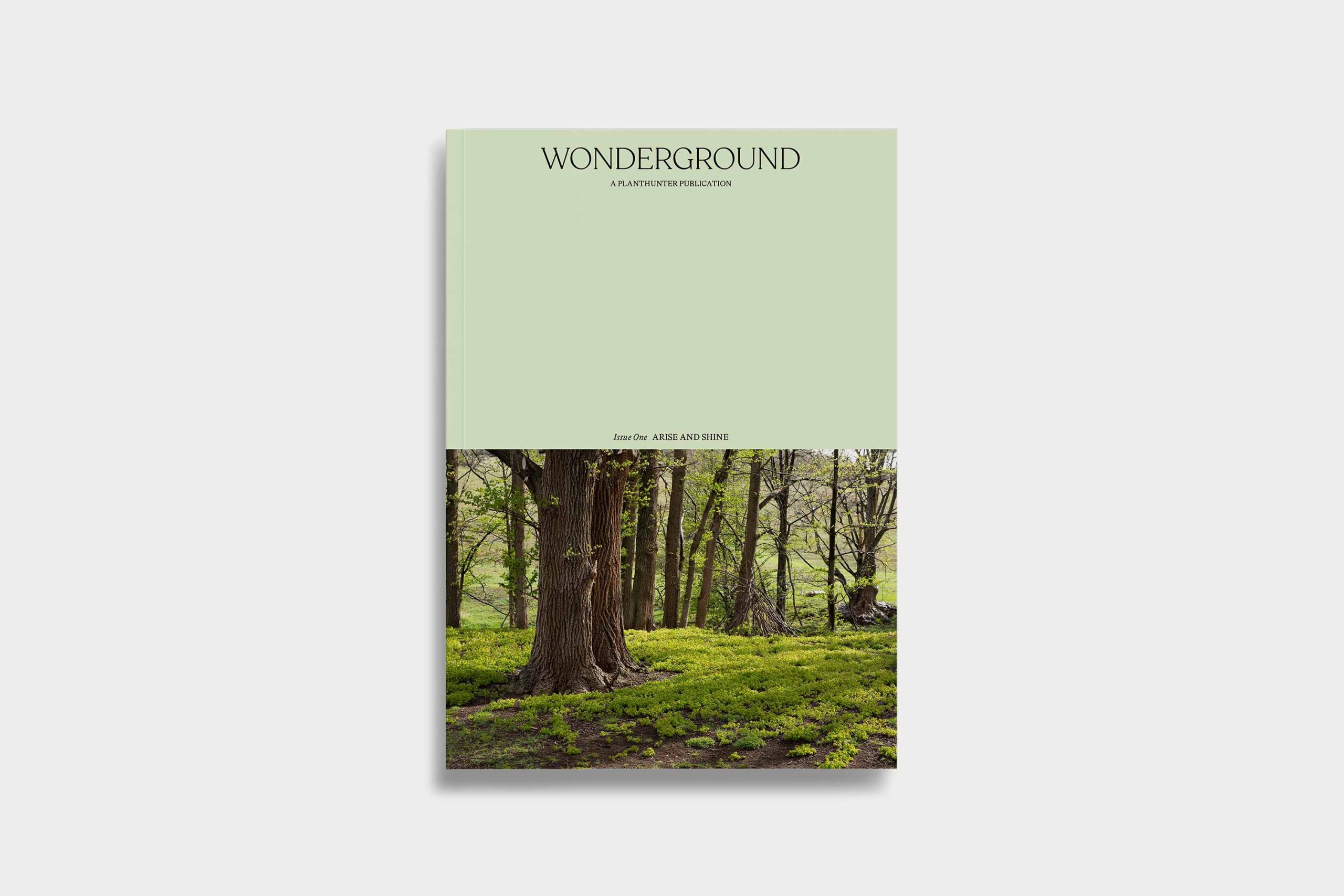

Post cover image by Jenny O.