The Art of Nature

- Words by

- Neha Kale

Artists have always been drawn to nature. But as the ecological moment sparks new questions about co-existence, contemporary artists are exploring the sentience and power of non-human life. Here’s an introduction to four contemporary artists navigating this territory – and uncovering new ways to think about plants, and ourselves, in the process.

NICHOLAS WILLIAM JOHNSON

Nicholas William Johnson has long been intrigued by the strange power of the natural world. As a teenager, the London-based artist, who was born in Hawaii and grew up in Vermont and Nova Scotia, was drawn to speculative fiction by writers like Ursula Le Guin and C.S. Lewis. They showed him that plants had wills of their own.

‘[In] Perelandra by C.S. Lewis, the protagonist eats a bit of seaweed and it gives him the perception of an undersea creature,’ he recalls. ‘I think there are so many ways to translate [plants] into images in whatever capacity. I’m always trying to evolve that.’

Johnson’s early work was interested in the ‘aesthetics of landscape and horror’. But since then, he’s made wildly inventive paintings that explore the otherworldly qualities of individual species. For Plant Communication Network, a 2018 exhibition at London’s Peter von Kant gallery, he rendered the Brugmansia or angel’s trumpet – a South American plant known for altering human perception – in swirling arrays of yellow, turquoise and blue.

‘I like the idea of poisonous plants as a subject because it gives the plant agency,’ he says. ‘We think of plants as something we prune to our desire but if a plant is inside you and doing something that you are not prepared for, it is in control.’

Johnson’s compositions decentre human ways of seeing. At the moment, the artist is making paintings that investigate plants that come to life in the dark.

‘I quite like this idea of what biologists call “vespertine” – plants that are fragrant at night,’ he says. ‘We have a couple of angel’s trumpets (Brugmansia spp.) and when we get ready for bed, they fill the flat with fragrance. It’s amazing how they have this inherent clock.’

RACHEL PIMM

The Western tradition has built a divide between nature and culture. But for Rachel Pimm, challenging well-worn binaries is less interesting than the possibilities of non-human life. The London-based artist explores landscapes and ecosystems – from the perspective of non-human agents such as plants and minerals.

Plates, a 2020 exhibition that showed at Whitechapel Gallery, features sound and images recorded in the Afar Triangle, an Ethiopian region that’s home to salt pans, hydrothermal fields and lava lakes. The work rejects patriarchal ideas of natural history in favour of something that’s symbiotic and more alive.

‘I was interested in the site being the beginning of the origin of life – it’s where the plates of the world diverged,’ they explain, adding that the show featured a soundtrack by experimental composer Lori E. Allen. ‘I got a bit bored of debates that did not further feminism, queer studies and antiracist work. It’s about how do you find this extremely messy landscape – and what can it tell us about how we can begin again.’

Pimm is wary of material production. Works such as 2019’s Earth Eating play with geophagy – the practice of ingesting soil. ‘We have to eat, right?’ they laugh. ‘I’ve been preparing meals made from mushrooms and salts and clays as a way of trying to experience environments rather than trampling on them.’

For Pimm, perceiving the natural world as conscious is also about unearthing histories that are easy to overlook. The artist’s 2019 installation, (The Great Exhibition of) The Work of Cash Crops, presented at the Serpentine Galleries, explored the relationship between rubber plantations in India and Britain’s colonial influence.

‘Plantation history is deeply related to extraction – plants are not just an analogy, they are the holders of this story,’ they say. ‘We used a [sonic device] “midisprout” to play the electrical impulses of the plants. You got to learn about the flow of energy that lives in [them].’

LINDA TEGG

For Linda Tegg, plants aren’t simply objects of study. They are living, breathing life forms that are led by designs of their own. In 2014, the acclaimed Australian artist conceived Grasslands, an installation that reimagined the precolonial grasslands that once thrived across Melbourne, on the steps of the city’s State Library. It taught her how plants can disrupt the best-laid human plans.

‘Grasslands was characterised by a sense of working with a plant community – I felt a particular kind of pressure from the plants,’ says Tegg, who cultivated 15,000 plants of sixty Indigenous species over fifteen months. ‘I’m interested in how plants disrupt our structures. From the threat a spontaneous plant poses to the fabric of the city to the vastly decentralised ways that a plant species might express itself. I hope that by acknowledging their existence we may open up new empathetic forms of living together.’

Tegg went on to show Repair, a work that evolved from Grasslands, at the Australian Pavilion at the 2018 Venice Biennale of Architecture. In the northern summer of 2020, she created a biodiverse meadowland in the car park outside ArkDes, Sweden’s national centre for architecture and design. Tegg says that the work, Infield, based on the term for the country’s premodern meadows, sees humans, plants and animals converge in a shared time and place.

‘The infield meadow became curious to me as its species richness is an unintended outcome of intensive human activity,’ she explains. ‘Plants have a lot to teach us about surviving in the conditions that humans create.’

DELFINA MUÑOZ DE TORO

Delfina Muñoz de Toro believes that nature exists beyond human understanding. She says that perceiving plants with your rational mind is like studying ‘a very small percentage of the sacred garden of the world’.

The Argentinian-born artist, Indigenist and musician makes dazzling paintings informed by ritual and ceremony, and rooted in ancient Amazonian traditions. For Muñoz de Toro, they offer a spiritual path.

‘I do not think of plants as humans, with a consciousness or sentience, but as beings, teachers and guides that should be highly respected,’ she says. ‘Each [has] their own energy and can heal, help, harm, open, protect, clean, nourish, firm the mind, clear the mind. [They] can give strength to your words, open the heart, give power, kill, poison, and more.’

Over the past few years, Muñoz de Toro has run art workshops across Indigenous villages in Acre, in the Brazilian Amazon. ‘We study the sacred geometries that are painted on the skin with natural pigments,’ she says. ‘[It’s] also about finding equilibrium between the older traditions and the newer, contemporary arts that are part of natural transformation and movement.’

She made The Root, a work that depicts a serpent wound around a tree, when the pandemic hit Brazil. The painting, which sees roots reach into the soil and exposes an underground universe to the viewer, showed as part of The Botanical Mind, a 2020 exhibition at London’s Camden Art Centre. Like much of her art, it arose out of a vision.

‘I had a vision of these gigantic live roots, moving like serpents and rising up as a tree,’ she says. ‘I rushed into a room and made a small sketch – it was so powerful.’

–

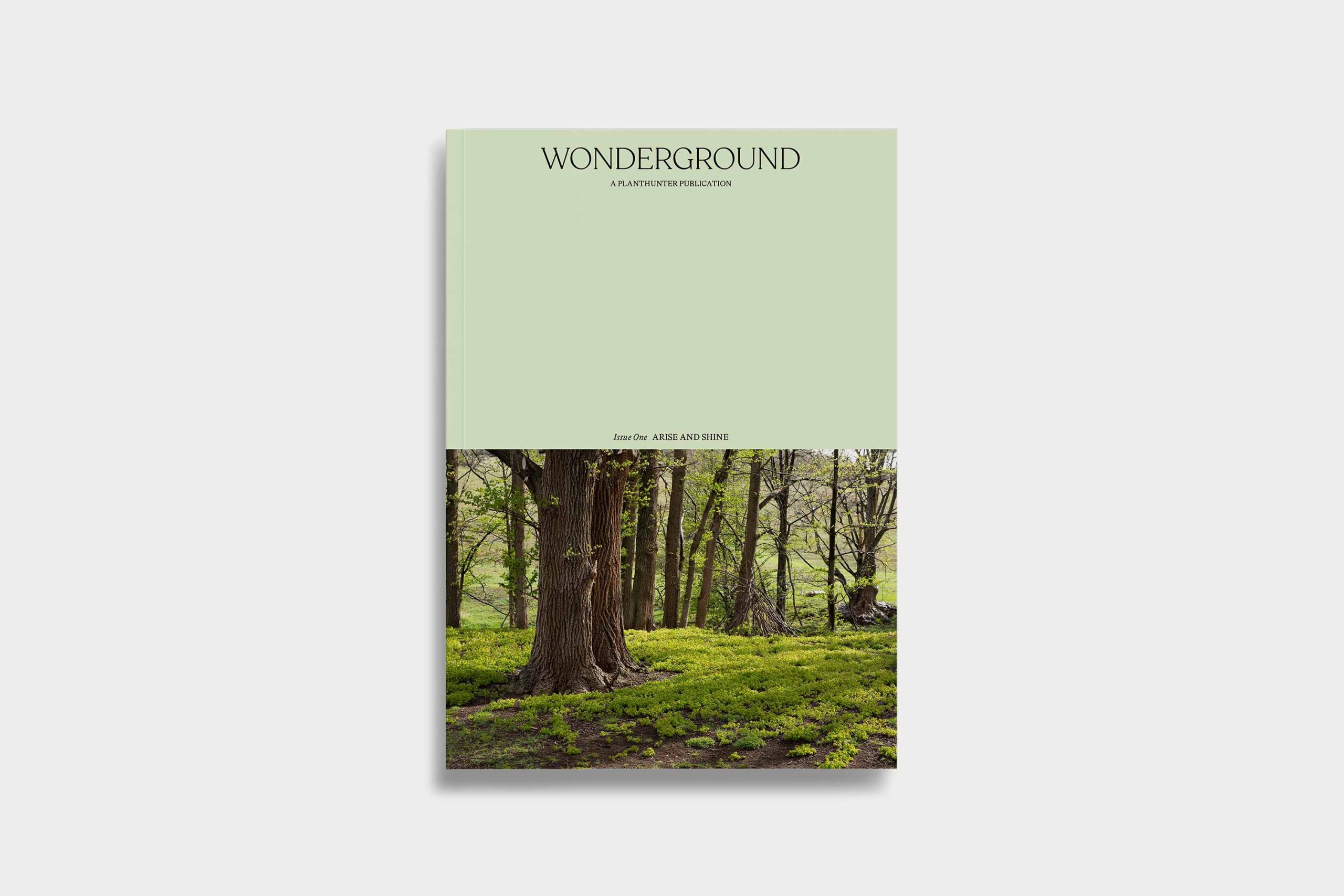

Post cover image: Repair, 2018, by Linda Tegg with Baracco Wright Architects, Australian Pavilion, 16th International Architecture Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia. Photo: Rory Gardiner